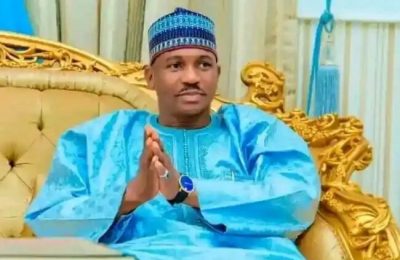

Senator Yahaya Oloriegbe is the chairman, Senate Committee on Health. In this interview with SADE OGUNTOLA, he speaks about his achievements in boosting health services and good governance, including the intervention of the 9th National Assembly in cancer care.

How many bills related to health have you supported in the 9th National Assembly, and why?

Based on my antecedent of leading a health reform organisation, advocating for change in the health sector between 2004 and 2008 and afterwards as a technical adviser to a minister of health, I have had an understanding of some of the challenges in the health sector and what reforms need to be pushed. For instance, I was part of the group of three people that drafted and pushed for the National Health Act in 2004, while still outside the government. It took 10 years for it to be passed. I was also opportune to be a major part of implementing its basic healthcare provision fund. This fund is a game changer in addressing primary health care in Nigeria now. This antecedent gave me the opportunity to have the knowledge, the idea and the passion to be able to promote, support and advocate for change in the health sector.

Now, when I now have the opportunity of being in the legislative arm of the government where laws are made and to lead a committee, I used the opportunity to bring on board those that are related to health. Of course, there are other bills that are not health-related that I proposed and had passed. Specifically, three of these bills were to create a fair share of federal opportunities in the constituency that I represent. One of the bills called the Psychiatry Hospital Amendment Bill is to establish a Federal Psychiatric Hospital in Budo-Egba in Kwara State. In the whole of the six states in North-Central, there was no single psychiatry hospital before I came on board. It was a lacuna because mental health is a major one and based on the World Health Organisation’s assessment, one in every four members of the population has one mental health problem or the other.

The central policy is that every state should have a Federal University, Federal Polytechnic and Federal College of Education. Kwara State has no Federal College of Education. The Old Kwara State used to have one but it is now situated in Kogi and Niger states. That was what prompted me to do that. The bill on the Federal College of Agriculture is for the same reason. These are issues that I was aware of before I got elected, and having understood the system, that prompted me to move those bills. Of course, there are two other bills that are not health-related and not of my constituency but of national interest. One is the bill on amendment to the CAMA Law. The law was passed in 2000. It gives power to the Corporate Affairs Commission to dissolve the board of trustees and appoint receivers as a general manager as if they are a company. Again, being the deputy chairman of the Senate Committee on Diaspora and its non-governmental organizations gave me the opportunity to move the amendment of that bill. It was a joint issue between my committee and the Committee on Trade and Investment.

Do you encounter problems raising these bills and ensuring that they are passed?

Of course, bills progression is associated with a lot of difficulties and challenges. A lawmaker is elected to make laws. With all sense of humility, my tenacity and commitment get the work done. It is not easy to move a bill from one stage to another. Bills pass through a minimum of five stages before it becomes a law. Already, four of my bills have become laws out of the 15 bills. Eleven had been passed by the Senate, and sent to the House of Representative for concurrence, and if there is no change from the House of Representatives, a clean copy is prepared and sent to the president for assent. Of course, it will go to the attorney-general’s office to see that there is no conflict between it and any other existing law. In fact, the National Health Insurance Authority was returned twice to the Senate and the House of Representatives for reconsideration before it eventually had the president’s assent. There are always problems along the line. Before a legislator has even one bill signed, it may take up to two years or even the whole session. In addition, the stages are long aside from the competitions between 109 senators and 360 House of Representatives members that have bills they also want listed to be heard and considered to be made into laws.

What is the extent of work on the Bill to Establish the Nigerian Medical Research Council?

The bill to establish the Nigerian Medical Research Council has passed the third reading at the Senate. Before the third reading, there was a public hearing with the Minister of Health, with his directors in attendance and other relevant agencies that were interested in the bill, including Nigerian Institute of Medical Research, National Institute of Pharmaceutical Research, Research Ethic Committee and so on. It was to get a harmonized version. Once the House gives it concurrence, because we have already carried along the Federal Ministry of Health, we should not have any problem in getting the president to sign it.

Of what significance is that bill to universal health coverage and quality health care delivery in Nigeria?

Medical practice generally is an application of what is called basic science knowledge to clinical sciences. So, without research, there cannot be new innovations to determine the effectiveness and appropriateness of medical devices and techniques that are already known. Without us funding research as a country, we will not be able to contribute to knowledge to be able to deliver quality service to Nigeria. We will only depend on research conducted by other countries. And of course, there are differences in the demographic structure and the epidemiology of diseases that are apparent in different countries. The health challenges we face are different. For instance, what happened here due to COVID-19 was different from what happened in say Europe, America or even Asian countries. So quality care without research cannot be achieved.

As the chairman Senate Committee on Health, what laws can be enacted to stem brain drain in the health sector?

First, brain drain is not only in the health sector; brain drain occurs in every sector. But the health sector is more prominent because globally we have a deficit of health workers. The problem is particularly more in the developing countries but developed countries are also affected; they are not able to produce the number of health workers they need. Similarly, the reason is because people are not going into science and it takes a longer time to be trained as a health professional. Of course, where demand is higher than the supply, there will be scarcity. That is why people are moving.

But more importantly, in our country, we don’t have enough. Even the few we have are moving out and few are retained. So we have to address why people move. There are several reasons; about three of them are major. Top on the list are remuneration, security and poor working environment. If the environment is not favourable, they will move to another environment. This includes getting the appropriate remuneration for the work done by the health professionals that is comparable to that in other countries with similar economic environments. But health workers are part of the public service of the government and their salary cannot just be raised. In addition to salaries, there should be incentives that can specifically be given through special law for them, like opportunities to have cars, housing through mortgage and special allowances for school for their children. This will encourage them to stay more than going out.

Again, people leave because of the working environment, including the necessary equipment to deliver services, basic social services and security. Certainly, it is not that one will just say this is one law to stem brain drain; it will be to look at the various causes of why people move out and see how we address it as a country. Mind you, even if we address those ones, we also still need to do one thing: we have to produce more. What we are producing now is relatively small compared to our population. There is a need for policies that will encourage people to go and study health sciences.

Nigeria’s budget for health is about six percent (of the national budget), less than 15 percent that it was a signatory to at the 2001 Abuja Convention. How can the legislators come in to ensure this?

It is only the executive that initiates the national budget; legislators don’t initiate the budget. The reason is because it is the executive that has the global picture of the revenue we have. The only thing is that the legislators make input, after that proposal. To achieve the Abuja 2001 Declaration is an executive policy because the executive gives priority to whatever it wants. As legislators, it is the appropriation committee specifically that can increase what comes from the executive, but usually this is done again with discussion with the executive. The budget system that we operate in Nigeria is an envelope system. For me, to achieve the Abuja Declaration, it is for the new government to increase its commitment to health. We might gradually increase it over the years until we get to 15 percent. But part of what we do as legislators when the budget comes is to advocate and engage the appropriation committee to give more to health. That is why we have been able to achieve the little that we are able to do.

Your committee at a time ensured the inclusion of cancer funds in the annual budget to support breast, prostate and cervical cancers in Nigeria. Where are we on this?

The funds started in 2020 and we are oversighting the ministry of health to implement it and there was a delay in its implementation. As such, the 2020 and 2021 monies were not utilized, but with pressure from us on the minister, implementation eventually started in 2022 in six teaching hospitals, one per geopolitical zone. People are already benefiting from it and the ministry intends to increase to two per geopolitical zone this year. The way it operates is that the fund is in the teaching hospital; they select people that are actually in need and cannot afford the cost of cancer treatment. We are following up the ministry regularly, including requesting for names of beneficiaries.

How have you been able to mix medicine with politics, given the need for health professionals to influence policies to ensure good health for all?

The mix of politics and medicine requires that people in the health profession generally go into politics. If you don’t have people with requisite qualifications, competency, skills and experience aspiring to be in governance, then we will not get it. I think that is part of the challenges we have in Nigeria. People should stop seeing politics as a dirty game; it is about passion and service. I had practised medicine for many years before I joined politics, and I have had wide experience in many fields. I see politics as a service to humanity, just like medicine. So, the populace should advocate for that. Secondly, the electorates need to be well enlightened to know and to also recognize those to elect into positions. Politics is still generally monetised; people don’t look at who will deliver the service that they need. As such, the leadership selection method is not able to pick such leaders. In the upcoming 10th assembly, to the best of my knowledge, there are two doctors elected to the Senate. Of course, there are other health professionals like pharmacists. In the current outgoing Senate, we are two doctors.