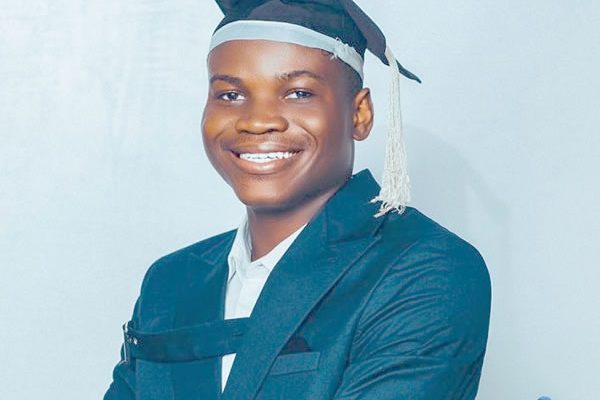

Vincent Ogbu graduated from the Faculty of Law, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, for the 2022 – 2023 session, with a First Class and a Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) of 4.7 on a scale of 5.00. In this interview by KINGSLEY ALUMONA, he speaks about his academic journey, the Nigerian legal system, among others.

During your secondary school days, what was your concept or idea of the law?

I have always been convinced that lawyers were solution-oriented people. Early in life, my elementary exposure was that lawyers were whom you could count on when things went south, that they were “assets that offset liabilities”. I grew up to have these rudimentary ideas validated.

I have always been convinced that my life’s path lies in being a lawyer. It could be that the books, journals, and newspaper clippings I found in my father’s room persuaded me that some of the greatest men to have led the country were lawyers. So, I started optimising early in life to be a lawyer.

In my teenage years, I remember trying to write a book about lawyers. I also argued vehemently in support of the “lawyers are better than doctors (or any other professions)” topic in school debates. My research in my senior secondary (SS) 3 days led me to believe that a career in law was the most feasible option for me.

My first impressionable moment with a lawyer who inspired me was in my junior secondary (JSS) 2. C.U. Mmuozoba, Esq, the current deputy director in charge of the Port Harcourt campus of the Nigerian Law School, came to deliver a keynote speech at our speech and prize-giving day. His keynote speech provided much-needed clarity for me that most of my nascent ambitious plans and goals in life were possible. I needed no other sign. I wanted to be a lawyer.

Why did you choose UNIZIK to study Law?

My choice of UNIZIK was influenced by my immediate elder brother, now Dr Ebuka Ogbu. I had initially wanted to go to the University of Lagos (UNILAG). Because I was an idealistic person those days, I relied on some of the lists published by websites on ‘top 10 universities in Nigeria’, etc. to choose tertiary institutions.

However, I am thankful for the advice of my brother, who showed me that cultural background, ease of settling into an environment, and societal norms were also crucial in picking a university.

What was your experience like studying law at UNIZIK?

I like to describe my experience in UNIZIK as commendably good from the lens of these three areas — academic coursework, experience and exposure, and network of friends and strategic contacts. As the years went by, it provided me the opportunity to put my growing intellectual capacity and repertoire of life skills to the test.

I encountered problems and challenges that tested me and pushed me to be better. In retrospect, I am grateful for the five years.

What aspect of your course interested you more?

I am enthusiastic about the law practice areas of media, energy, and technology. In general, I am curious and always eager to know how the instrumentality of the law can be applied to solve and address complex problems that arise in multi-border business operations and transactions. I am excited when I come across scenarios and legal issues that showcase the lacunas in the laws of countries. In these cases, I try to evolve solutions and possible legal answers to these loopholes and lacunas.

I believe that law is a key driver of growth and development, as it dictates and directs the pace of innovation.

To make a First Class in Law is not easy. How did you manage to achieve this feat?

I have dedicated an entire essay to this topic, titled ‘A first-class law degree: How I did it and why I recommend it’, which can be found on my Medium page. In the article, I focused on the role of a plan-map and the grades triangle — coursework-lecturers-you — to be pivotal to academic success.

I would say the mix of critical planning (using a ‘plan-map’), continuous study and proactive reading (instead of reactive reading), stimulating your examinations before the exams, diligence and hard work would earn one the academic glory they desire.

Lastly, a key template is stimulating examinations on a self-assessed basis before the actual exams. This helps you grade your readiness and fine-tune areas that need to be addressed in your readiness for examinations. Overall, I encourage law students, preferably freshmen, to be inquisitive.

What were your moot court experiences like?

My first moot court case was an external appearance at the University of Nigeria (UNN), Nsukka, where I and some of my classmates represented my school in their new wigs competition in 2020. It was a moot scenario bordering on the rights of a parent to refuse treatment for their ward on the grounds of religious belief, and I remember it clearly because I argued ‘Necessity’ as an exception that would warrant a derogation from the fundamental rights of a person.

My team came a close second, behind the host UNN, and Enugu State University of Technology (ESUT) came third.

After that, I went on to engage in competitive mooting, going undefeated in local moot competitions I appeared at my university level. I remember winning the New Wigs moot competition at my university and winning the November 2021 Law Faculty Chambers’ moot competition for my student chambers, Liberty Chambers, alongside my moot partner, Goodluck Aguiyi. Goodluck Aguiyi is a noteworthy mention, as I appeared in all my competitive mooting in the faculty with him. A four-time winning streak.

I also participated in inter-university mooting and competitions. The one that readily comes to mind would be the 2022 Nigerian National Rounds of the popular Manfred Lachs International Space Law competition, held in Abuja, where I was an oralist for my school. Though my team didn’t make it to the next round, it was an exhilarating experience.

What was the title of your final-year project and what were the major findings from it?

My best course was Energy and Natural Resources Law, and I picked it to be the course for my final-year long essay.

My project topic was ‘An analysis of the legal implications of the innovations in the Petroleum Industry Act’.

My long essay x-rayed the innovations pioneered by the Act across its regulatory, institutional, operational, fiscal/monetary, and social provisions, and their legal impact on government regulators, petroleum industry players, and other relevant stakeholders.

The findings showcase that while regulatory and governance issues were addressed by the Act, there is no real socio-economic impact on the lives of ordinary Nigerians. The Act may have solved old problems plaguing the oil sector, but it has inadvertently “created new issues.”

What major academic and infrastructural challenges in UNIZIK made your studentship less memorable?

Learning facilities and classroom spaces are two key areas I would recommend my alumni university to work on. I understand that there are concerted efforts made by the present university administration to address learning space problems. I would also suggest more face time and increased forum interface between the students and lecturers, especially those in administrative positions.

The area of promptly providing students with their results is one area I would lend my voice. Most students apply for internships, scholarships and/or grants, and often require their academic records or transcripts as one of the complying requirements. Faculties and departments must make provisions, in terms of support staff and ease of access to this.

Many people who study law end up not practising it. Would you be a practising lawyer?

I like to regard myself as a transactions lawyer. I would like to be highly regarded in the practice areas of technology, media, and energy law. I am excited by complex problems in fast-moving industry sectors and would like to be the go-to lawyer in complicated legal issues that arise in business transactions and deals advisory.

There are many unfair judgments meted out to common people in Nigerian law courts. So, to you, is the saying, “The law is the last hope of the common man” still tenable?

Of course, it is still tenable. At the risk of sounding technical and formal, I want to reference the words of the Court of Appeal in OBAJIMI v. ADEDIJI (2008), where the appellate court held, “Justice means fair treatment, and justice in any case, demands that the competing rights of the parties must be taken into consideration and balanced in such a way that justice is not only done but must be seen to be done.”

In any case, it is important to note that justice is a two-way street — both to the complainant and the accused, a claimant and a defendant, etc. What our courts have been known to do over time is pronounce based on the preponderance of evidence before it or as parties before the courts have proved their case.

I must acknowledge the latent defects such as delays, operational inefficiencies, and lapses that plague our justice delivery system and generally believe that the interventions by the judiciary leadership in Nigeria is addressing the problems as they arise.

You are familiar with the Nigerian law and legal system. If you were to recommend reforms that would make it better, what would they be?

A key reform I would recommend is true federalism and re-adapting our legal system to be truly federalist through a de-concentration of powers at the federal level. We are a multicultural and heterogeneous country, and true growth and development should be competitive at the state and local government levels. Our laws are highly centralised as it stands. This should not be so.

Among the prominent Nigerian lawyers that you know, who among them are your role models?

I look up to lawyers who have used their law career, not just as a career per se, but as a ‘carrier’ to places, positions, and generally a diversified portfolio. A clear example of this is Adebayor Ogunlesi. I am highly inspired by his life’s work and career sojourn.

READ ALSO: VIDEO: ‘My dad can’t afford my school fee,’ eight-year-old boy joins protest in Lagos